Types of Stars

There are many different types of stars in the Universe, from Protostars to Red Supergiants. They can be categorized according to their mass and temperature.

Stars are also classified by their spectra (the elements they absorb). Along with their brightness (apparent magnitude), the spectral class of a star can tell astronomers a lot about it.

There are seven main types of stars. In order of decreasing temperature, O, B, A, F, G, K, and M. O and B are uncommon, very hot and bright. M stars are more common, cooler, and dim.

The video below presents a helpful overview of the types of stars in the Universe.

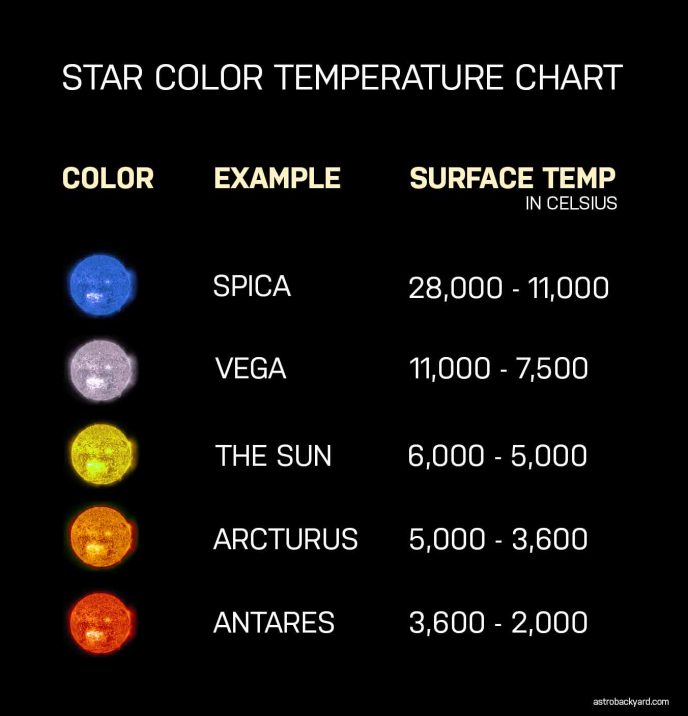

Although there are scientific reasons why stars are different colors and sizes, everyone can enjoy this reality by simply looking up at the night sky.

You’ll notice that some stars have a warm, orange appearance (such as Betelgeuse in the constellation Orion), and others have a cool, white appearance (like Vega in the constellation Lyra).

Through astrophotography, I can enjoy seeing the many different types of stars in the Universe.

The photo below is one of my favorite examples of the different types of stars in the night sky. The constellation Orion has countless stars of varying temperatures.

The colorful stars in the constellation Orion. Trevor Jones

Beauty aside, there are fascinating underlying reasons why stars have different colors in the night sky. A star’s size and color depend on its age and life-cycle stage.

There are 7 different types of stars:

The 7 Main Spectral Types of Stars:

- O (Blue) (10 Lacerta)

- B (Blue) (Rigel)

- A (Blue) (Sirius)

- F (Blue/White) (Procyon)

- G (White/Yellow) (Sun)

- K (Orange/Red) (Arcturus)

- M (Red) (Betelgeuse)

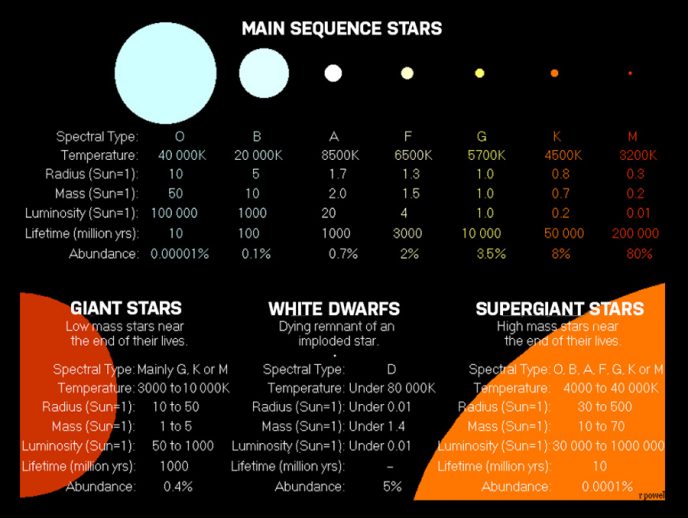

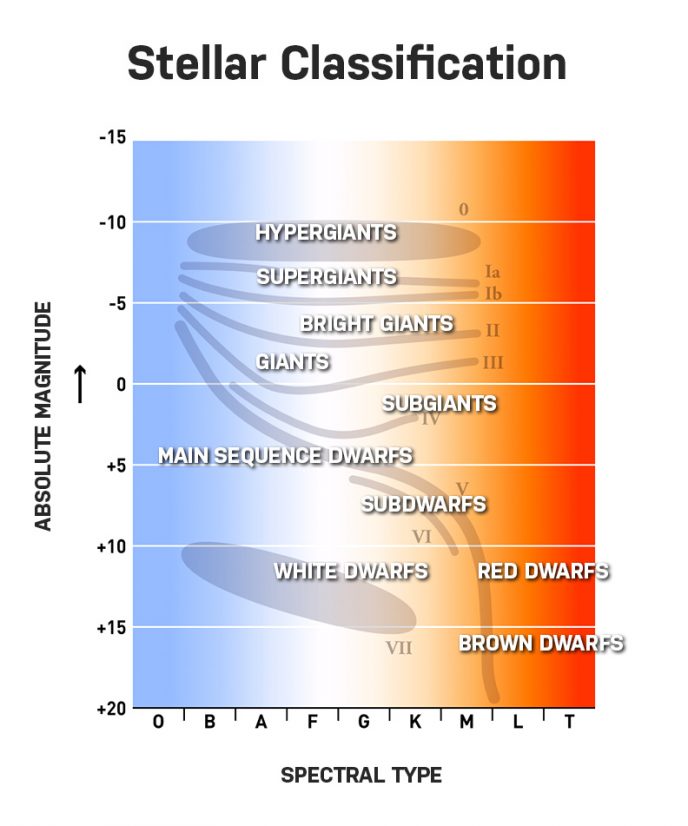

The diagram below shows most of the major types of stars (the majority of stars are main sequence stars). Stars just like our own Sun that burn hydrogen into helium to produce energy.

This diagram shows the typical properties for each type of star.

The classification of Stars (Atlas of the Universe).

This system is referred to as the Morgan Keenan system. The Morgan-Keenan (MK) system is used in modern astronomy a classification system to organize stars according to their spectral type and luminosity class. The system was introduced by William Wilson Morgan and Philip C Keenan in 1943.

What is the Most Common Type of Star?

When you look up the night sky on a clear night, it may seem as if most stars are cool, blue stars that would fall under the B, or A class of stars. However, main-sequence Red dwarf stars are the most common kind of stars in our Universe.

Our own Sun is a main-sequence, G-type star, but most of the stars in the Universe are much cooler and have low mass. In fact, most of the main-sequence Red dwarfs are too dim to be seen with our naked eye from Earth.

Red dwarfs burn slowly, meaning they can live for a long time, relative to other star types.

The closest star to Earth (Proxima Centauri), is a Red dwarf. Red dwarfs include the smallest of the stars in the Universe, weighing between 7.5% and 50% the mass of the Sun.

Although main-sequence Red dwarfs are the most common stars in the universe, there are 7 main types of stars in total. Here is some information about each type of known star in our universe.

Below, is a simple star color temperature chart that provides examples of some of the most well-known stars in the night sky, and their colors.

Protostar:

A protostar is what you have before a star forms. A protostar is a collection of gas that has collapsed down from a giant molecular cloud.

The protostar phase of stellar evolution lasts about 100,000 years. Over time, gravity and pressure increase, forcing the protostar to collapse down.

All of the energy released by the protostar comes only from the heating caused by the gravitational energy – nuclear fusion reactions haven’t started yet.

The Birth of Star (Video)

T Tauri Star:

A T Tauri star is a stage in a star’s formation and evolution right before it becomes a main-sequence star.

This phase occurs at the end of the protostar phase when the gravitational pressure holding the star together is the source of all its energy.

T Tauri stars don’t have enough pressure and temperature at their cores to generate nuclear fusion, but they do resemble main-sequence stars; they’re about the same temperature but brighter because they’re larger.

T Tauri stars can have large areas of sunspot coverage, and have intense X-ray flares and extremely powerful stellar winds. Stars will remain in the T Tauri stage for about 100 million years.

Main Sequence Stars

Main Sequence stars are young stars. They are powered by the fusion of hydrogen (H) into helium (He) in their cores, a process that requires temperatures of more than 10 million Kelvin.

Around 90 percent of the stars in the Universe are main-sequence stars, including our sun. The main sequence stars typically range from between one-tenth to 200 times the Sun’s mass.

A star in the main sequence is in a state of hydrostatic equilibrium. Gravity is pulling the star inward, and the light pressure from all the fusion reactions in the star are pushing outward.

The inward and outward forces balance one another out, and the star maintains a spherical shape. Stars in the main sequence will have a size that depends on their mass, which defines the amount of gravity pulling them inward.

Blue Stars

Blue stars are typically hot, O-type stars that are commonly found in active star-forming regions, particularly in the arms of spiral galaxies, where their light illuminates surrounding dust and gas clouds making these areas typically appear blue.

Blue stars are also often found in complex multi-star systems, where their evolution is much more difficult to predict due to the phenomenon of mass transfer between stars, as well as the possibility of different stars in the system ending their lives as supernovas at different times.

Blue stars are mainly characterized by the strong Helium-II absorption lines in their spectra, and the hydrogen and neutral helium lines in their spectra that are markedly weaker than in B-type stars.

Because blue stars are so hot and massive, they have relatively short lives that end in violent supernova events, ultimately resulting in the creation of either black holes or neutron stars.

Red Dwarf Star

Red dwarf stars are the most common kind of stars in the Universe. These are main-sequence stars but they have such low mass that they’re much cooler than stars like our Sun.

This cooler state makes them appear faint. They have another advantage. Red dwarf stars are able to keep the hydrogen fuel mixing into their core, and so they can conserve their fuel for much longer than other stars.

Astronomers estimate that some red dwarf stars will burn for up to 10 trillion years. The smallest red dwarfs are 0.075 times the mass of the Sun, and they can have a mass of up to half of the Sun.

What is a Red Dwarf Star? (Video)

Yellow Dwarfs

A yellow dwarf is a star belonging to the main sequence of spectral type G and weighing between 0.7 and 1 times the solar mass.

About 10% of stars in the Milky Way are dwarf yellow. They have a surface temperature of about 6000 ° C and shine a bright yellow, almost white.

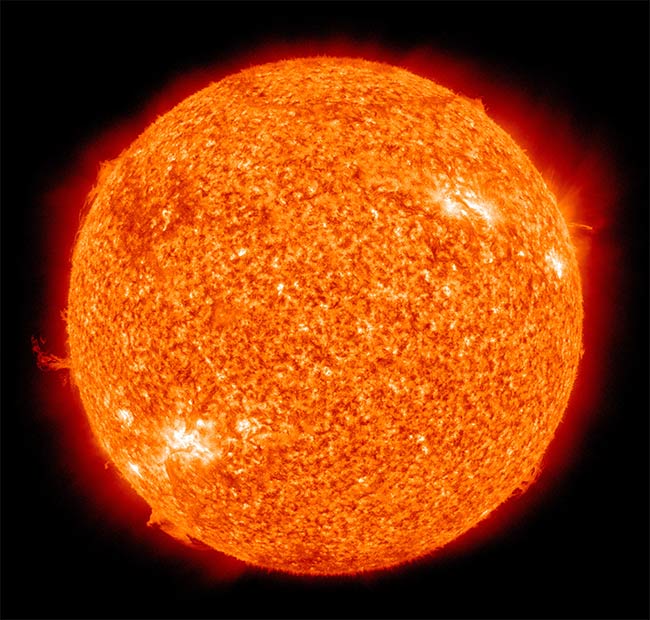

Our Sun is an example of a G-type star, but it is, in fact, white since all the colors it emits are blended together.

The Sun is an example of a G-type main-sequence star (yellow dwarf). NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory.

Nonetheless, even though all the Sun’s visible light is blended to produce white, its visible light emission peaks in the green part of the spectrum, but the green component is absorbed and/or scattered by other frequencies both in the Sun itself and in Earth’s atmosphere.

Typical G-type stars have between 0.84 and 1.15 solar masses, and temperatures that fall into a narrow range of between 5,300K and 6,000K.

Like the Sun, all G-type stars convert hydrogen into helium in their cores, and will evolve into red giants as their supply of hydrogen fuel is depleted.

Orange Dwarfs

Orange dwarf stars are K-type stars on the main sequence that in terms of size, fall between red M-type main-sequence stars and yellow G-type main-sequence stars.

K-type stars are of particular interest in the search for extraterrestrial life, since they emit markedly less UV radiation (that damages or destroys DNA) than G-type stars on the one hand, and they remain stable on the main sequence for up to about 30 billion years, as compared to about 10 billion years for the Sun.

Moreover, K-type stars are about four times as common as G-type stars, making the search for exoplanets a lot easier.

Supergiant Stars:

The largest stars in the Universe are supergiant stars. Giants and supergiants form when a star runs out of hydrogen and begins burning helium.

As the star’s core collapses and gets hotter, the resulting heat subsequently causes the star’s outer layers to expand outwards.

The Biggest Stars in the Universe (Video)

Low and medium-mass stars then evolve into red giants. However, high-mass stars 10+ times bigger than the Sun become red supergiants during their helium-burning phase.

Supergiants are consuming hydrogen fuel at an enormous rate and will consume all the fuel in their cores within just a few million years.

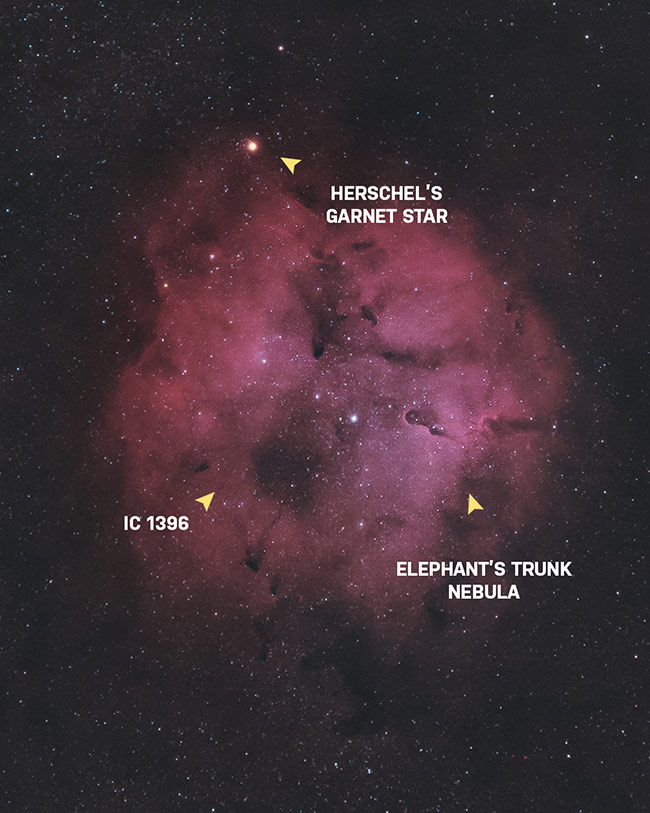

An example of a red supergiant star is Herschel’s Garnet star in Cepheus. The Garnet Star, Mu Cephei, appears garnet red and is located at the edge of the IC 1396 nebula.

A photo of IC 1396 (emission nebula) in Cepheus showing the Red Supergiant star, Mu Cephei.

Mu Cephei is visually 100,000 times brighter than our Sun, with a magnitude of −7.6.

Supergiant stars live fast and die young, detonating as supernovae; completely disintegrating themselves in the process.

Blue Giants

Stars with luminosity classifications of III and II (bright giant and giant) are referred to as blue giant stars.

The term applies to a variety of stars in different phases of development. They are evolved stars that have moved from the main sequence but have little else in common.

Therefore blue giant simply refers to stars in a particular region of the HR diagram rather than a specific type of star. An example of a blue/white giant star is Alcyone in the constellation Taurus.

Blue giants are much rarer than red giants, because they only develop from more massive and less common stars, and because they have short lives. Some stars are mislabelled as blue giants because they are big and hot.

Blue Supergiants

Blue supergiant stars are scientifically known as OB supergiants, and generally have luminosity classifications of I, and spectral classifications of B9 or earlier.

Blue supergiant stars are typically larger than the Sun, but smaller than red supergiant stars, and fall into a mass range of between 10 and 100 solar masses.

Typically, type-O and early type-B main sequence stars leave the main sequence in only a few million years, since they burn through their supply of hydrogen very quickly due to their high masses.

These stars start the process of expansion into the blue supergiant phase as soon as heavy elements appear on their surfaces, but in some cases, some stars evolve directly into Wolf–Rayet stars, skipping the “normal” blue supergiant phase.

Red Giants

When a star has consumed its stock of hydrogen in its core, fusion stops and the star no longer generates an outward pressure to counteract the inward pressure pulling it together.

A shell of hydrogen around the core ignites continuing the life of the star but causes it to increase in size dramatically. In these stars, hydrogen is still being fused into helium, but in a shell around an inert helium core.

The aging star has become a red giant star and can be 100 times larger than it was in its main sequence phase. When this hydrogen fuel is used up, further shells of helium and even heavier elements can be consumed in fusion reactions.

The red giant phase of a star’s life will only last a few hundred million years before it runs out of fuel completely and becomes a white dwarf.

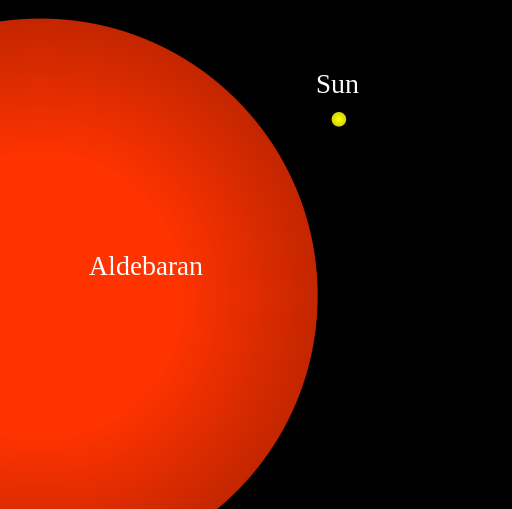

Aldebaran is a Red Giant star that is 44 times the radius of the Sun. Wikipedia.

Red Supergiants

Red supergiant stars are stars that have exhausted their supply of hydrogen at their cores, and as a result, their outer layers expand hugely as they evolve off the main sequence.

Stars of this type are among the biggest stars known in terms of sheer bulk, although they are generally not among the most massive or luminous.

Antares, in the constellation Scorpius, is an example of a red supergiant star at the end of its life.

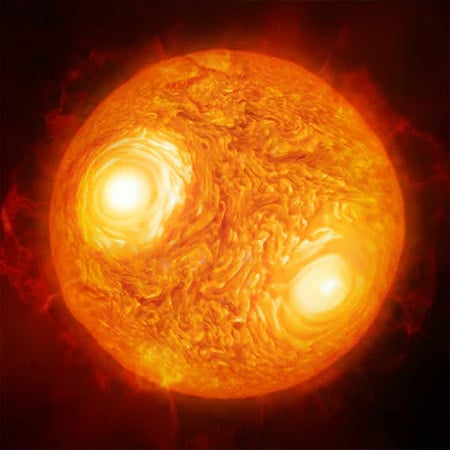

An artists rendering of Antares, a red supergiant star (Inverse.com).

White Dwarfs

When a star has completely run out of hydrogen fuel in its core and it lacks the mass to force higher elements into fusion reaction, it becomes a white dwarf star.

The outward light pressure from the fusion reaction stops and the star collapses inward under its own gravity. A white dwarf shines because it was a hot star once, but there’s no fusion reactions happening anymore.

A white dwarf will just cool down until it becomes the background temperature of the Universe. This process will take hundreds of billions of years, so no white dwarfs have actually cooled down that far yet.

Neutron Stars

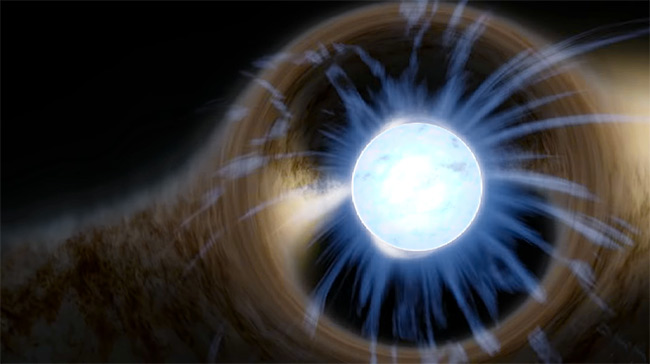

Neutron stars are the collapsed cores of massive stars (between 10 and 29 solar masses) that were compressed past the white dwarf stage during a supernova explosion.

A simulated view of a neutron star (Wikipedia).

The remaining core becomes a neutron star. A neutron star is an unusual type of star that is composed entirely of neutrons; particles that are marginally more massive than protons, but carry no electrical charge.

Neutron stars are supported against their own mass by a process called “neutron degeneracy pressure”. The intense gravity of the neutron star crushes protons and electrons together to form neutrons.

If stars are even more massive, they will become black holes instead of neutron stars after the supernova goes off.

Black Holes

While smaller stars may become a neutron star or a white dwarf after their fuel begins to run out, larger stars with masses more than three times that of our sun may end their lives in a supernova explosion.

The dead remnant left behind with no outward pressure to oppose the force of gravity will then continue to collapse into a gravitational singularity and eventually become a black hole, with the gravity of such an object so strong that not even light can escape from it.

There are a variety of different black holes. Stellar-mass black holes are the result of a star around 10 times heavier than the Sun ending its life in a supernova explosion, while supermassive black holes found at the center of galaxies may be millions or even billions of times more massive than a typical stellar-mass black hole.

Known examples of black holes include Cygnus X-1 and Sagittarius A.

Brown Dwarfs

Brown Dwarfs are also known as failed stars. This is due to the result of their formation. Brown Dwarfs form just like stars.

However, unlike stars, brown dwarfs do not have sufficient mass to ignite and fuse hydrogen in their cores. They, therefore, don’t shine and can be small.

Typically, brown dwarf stars fall into the mass range of 13 to 80 Jupiter-masses, with sub-brown dwarf stars falling below this range.

Stellar Classification Chart (Hertzsprung–Russell diagram). Wikipedia.

Star Lifecycle:

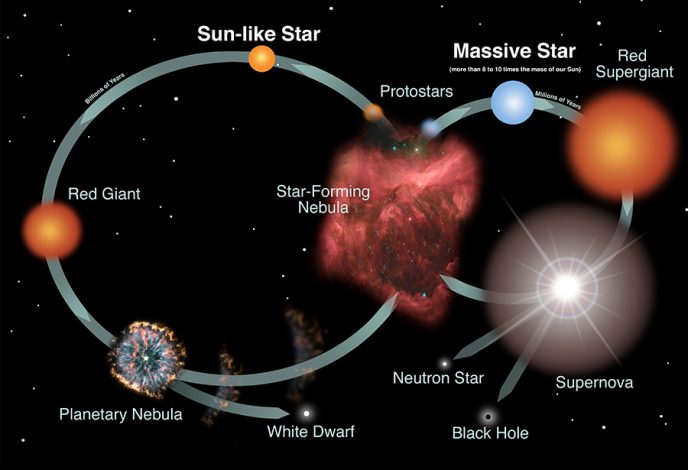

The following diagram os a fantastic visual reference to use when describing the lifecycle of Sun-like and massive stars. It is fascinating to see the transition between the nebulae stages of the star-forming process to a red supergiant or even a new planetary nebula.

The lifecycle of a star (NASA and the Night Sky Network).

Binary Stars:

Double Star

A double star is two stars that appear close to one another in the sky. Some are true binaries (two stars that revolve around one another); others just appear together from the Earth because they are both in the same line-of-sight.

Binary Star

A binary star is a system of two stars that rotate around a common center of mass. About half of all stars are in a group of at least two stars.

Polaris is part of a binary star system.

Eclipsing Binary

An eclipsing binary is two close stars that appear to be a single star varying in brightness. The variation in brightness is due to the stars periodically obscuring or enhancing one another. This binary star system is tilted (with respect to us) so that its orbital plane is viewed from its edge.

X-Ray Binary Star

X-ray binary stars are a special type of binary star in which one of the stars is a collapsed object such as a white dwarf, neutron star, or black hole. As matter is stripped from the normal star, it falls into the collapsed star, producing X-rays.

Variable Stars – Stars that Vary in Luminosity:

Cepheid Variable Star

Cepheid variables are stars that regularly pulsate in size and change in brightness. As the star increases in size, its brightness decreases; then, the reverse occurs. Cepheid Variables may not be permanently variable; the fluctuations may just be an unstable phase the star is going through. Polaris and Delta Cephei are examples of Cepheids.

Galaxies that were once thought to be “spiral nebulae” such as the Whirlpool Galaxy were re-classified when Edwin Hubble was able to observe Cepheid variables in some of these spiral nebulae.